Plunging offshore wind costs spur higher US growth outlooks

Falling costs in Europe are prompting US. offshore wind developers to raise growth outlooks but faster deployment will require accelerated supply chain and infrastructure support, company executives said at the U.S. Offshore Wind 2017 conference on May 8.

Related Articles

On May 11, the Maryland Public Service Commission (PSC) awarded offshore wind renewable energy credits (ORECs) to the 248 MW U.S. Wind and 120 MW Skipjack Offshore Energy projects, expected to be first large-scale offshore windfarms in the U.S. The projects will receive a 20-year levelized price of $131.93/MWh and experience in Europe has shown that the cost of subsequent U.S. projects will drop as developers gain from economies of scale and growing industry infrastructure.

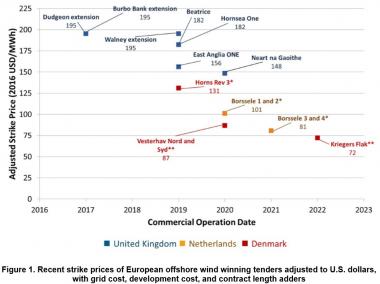

Vattenfall's record-low offshore wind price of 37.2 ore per kWh [49.9 euros/MWh, $53/MWh] for the 600 MW Kriegers Flak project in Denmark last November showed how falling costs and competitive tenders are spurring intense price competition in the European offshore wind market.

In April, DONG Energy and ENBW became the first offshore wind power developers to acquire offshore wind power concessions at unsubsidized prices. DONG and ENBW bid prices of Eur0/MWh for 1.4 GW of German offshore wind capacity, exposing the projects to wholesale market prices when they are completed in 2024 and 2025.

European offshore tender prices in US $

(Click image to enlarge)

Source: National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). Data source 4Coffshore

Bloomberg New Energy Finance has predicted up to 4 GW of offshore wind capacity could be installed in the U.S. by 2030 but global costs are falling faster than expected and these forecasts may underestimate deployment rates, Sven Utermohlen, Chief Operating Officer of E.ON Climate & Renewables, told the conference in New York.

"If the competitiveness of the business case is supported, there might actually be a lot more growth," he said. E.ON has stakes in nine offshore wind farms in Europe and owns over 1 GW of operational capacity.

According to Doug Pfeister, Managing Director of Renewables Consulting Group, the U.S. could procure over 5 GW of offshore wind projects by 2025 and as much as 11 GW by 2030.

These projections assume several states not currently active in offshore wind-- including those on the West Coast-- will launch market development to achieve carbon reduction goals and renewable portfolio standard (RPS) targets, Pfeister told the conference.

"When you do the math, you can see that they are not going to get there without offshore wind," he said.

Market openings

Rising turbine capacities and growing project scale are reducing installation costs and increasing investor confidence in the offshore wind sector.

High costs held back European offshore growth for a number of years, but recent cost reductions have opened up new markets, Utermohlen said.

"It feels like we have unlocked a lot of potential," he said.

A significant number of U.S. power plants will need to be replaced in the coming years and reductions in offshore wind costs have made the technology more competitive than nuclear and coal-fired generation, Stephen Bull, Senior Vice President of Statoil’s Wind & Carbon Capture and Storage business, told the conference.

"This is going to open up [offshore capacity] numbers that we really didn't dream of," Bull said.

Forecast US generation capacity additions

Source: EIA's Annual Energy Outlook 2017.

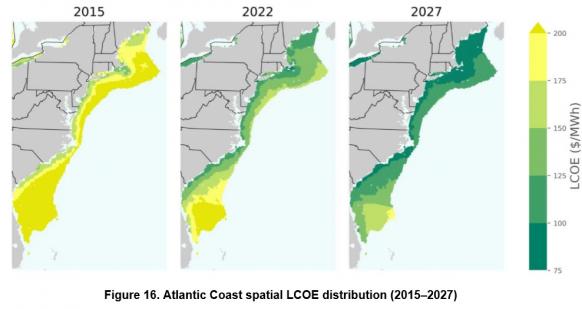

A recent study by the U.S. National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) has shown that U.S. offshore wind plants could be built on an unsubsidized basis by the late 2020s.

"We are seeing significant cost reductions towards [unsubsidized] economic potential," Walter Musial, Offshore Wind Manager at NREL, told the conference.

NREL estimates by 2027 there is potential for 65 GW of economically viable (unsubsidized) offshore wind capacity just in the state of Maine, and 55 GW in Massachusetts.

NREL based its economic potential projections on the localized net value of plants, represented by the difference between the forecast levelized avoided cost of energy (LACE) to the grid and the levelized cost of energy (LCOE).

Forecast East Coast offshore wind LCOE

Source: NREL (2017)

LACE was estimated based on locational marginal wholesale prices and regional energy deployment system (ReEDS) models while LCOE calculations used cost models for 7,000 U.S. sites, including variables such as water depth, wind resource, substructure type, turbine size, distance to port, distance to cable interconnect, installation method, and sea state. Future costs were calculated using 50 cost reduction variables.

NREL's calculations do not include government support for offshore wind projects, such as tax credits or subsidized offtake contracts, and the estimates will need to be updated to account for plummeting strike prices seen in Europe's latest offshore wind tenders, Musial said.

"We are in the process of developing risk profiles to understand how these strike prices can be translated into U.S. costs...Taking our unsubsidized economic potential numbers and putting that into a framework where we can capture risk and [government] policy is probably our next step," he said.

Growth hurdles

While falling costs have raised the potential for U.S. offshore wind deployment, growth rates will depend on the planning and buildout of supply chain and infrastructure.

In the early stages of European offshore wind market development, the supply chain was relatively inexperienced and companies adapted existing technologies and vessels, Utermohlen said.

"I think we have to make sure in the U.S. we jump over that period immediately," he said.

U.S. offshore participants must establish without delay a fit-for-purpose harbor infrastructure close to the offshore sites, put in place a specialized high-quality supply chain, and place orders for U.S. market vessels, Utermohlen said.

In addition, regulatory authorities must set out clear transmission grid access regulations and support power purchase agreements (PPAs) at prices which support current project costs, he said.

The buildout of utility scale projects in Maryland should be followed by projects in Massachusetts and New Jersey and this sequence of projects will boost supply chain development and maximize economies of scale, Paul Rich, Director of Project Development at US Wind, said.

"Sequencing will be important...This would substantiate the most optimistic [capacity predictions]," he said.

Federal government authorities must support offshore wind developers with efficient instruction planning to help raise economies of series and scale and reduce the need for government subsidies, Rich said.

"We are ready to go. Facilities up and down the East Coast either need to be converted to this new industry to support it, or start from new, but they do exist as a natural resource," he said.

New Energy Update